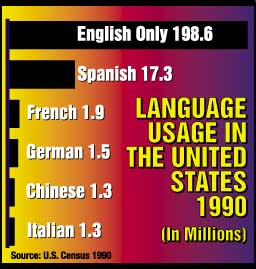

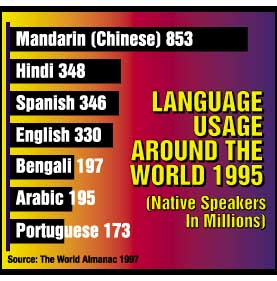

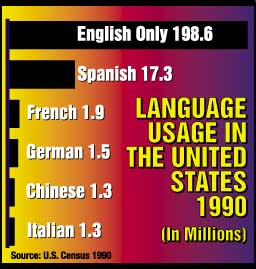

Spanish is on the rise. The

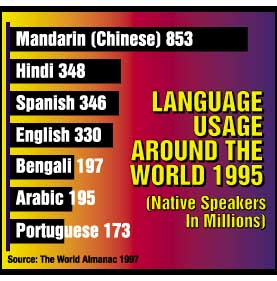

numbers might surprise you. Spanish is No. 3 among the more than 5,000

languages spoken in the world today. Only the languages

of China and India are spoken by more native speakers. Even English take

a back seat to Spanish with 330 million native speakers in the world, compared

to 346 million for Spanish.

In the United States, college students are flocking to learn the language.

Major U.S. book companies are publishing Spanish-language editions, available

at your local Borders bookstore. Corporate America is increasingly selling

itself through Spanish-language ads, and following the lead of CNN en Español,

new arrival CBS Telenoticias is competing head-to-head with Univisión

and Telemundo for U.S. and Latin American Spanish-speaking audiences. And

immigration continues to swell the ranks of Spanish speakers in this country.

There were more than 17 million of them by 1990, more than the combined

total of speakers of all other non-languages.

Despite

the boom in Spanish, no one questions the continuing dominance of English

in the United States and internationally. English is the lingua franca

in the world today. Its status is ensured by its use in cutting-edge areas

such as science, aviation, and computers. Checking out the Internet's World

Wide Web? About 83 percent of home pages are in English. No language in

human history has ever had the global standing English currently enjoys.

Despite

the boom in Spanish, no one questions the continuing dominance of English

in the United States and internationally. English is the lingua franca

in the world today. Its status is ensured by its use in cutting-edge areas

such as science, aviation, and computers. Checking out the Internet's World

Wide Web? About 83 percent of home pages are in English. No language in

human history has ever had the global standing English currently enjoys.

A Question of Long-term Health

What is in question is the future of Spanish in this

country. Beneath the upbeat statistics, there are serious concerns about

its long-term health. Studies show that the failure of many second- and

third-generation Latinos to retain the language is depleting the pool of

Spanish speakers. Yet that same pool is continually replenished by immigration.

What will be the ultimate outcome of these seemingly contradictory trends?

The

fate of immigrant languages has been to flower, then fade. Will that be

the story of Spanish in the next century? Many experts believe it already

is happening. They say immigration merely prolongs the inevitable. Since

large-scale Latin American immigration will not continue forever, they

contend, Spanish in the United States will eventually decline. Only major

changes in language attitudes and policies will prevent this. They point

out that a script similar to that followed by previous immigrants is being

played out as U.S.-born Hispanics, for whom English is almost always the

language of choice, seldom pass on Spanish to their offspring.

The

fate of immigrant languages has been to flower, then fade. Will that be

the story of Spanish in the next century? Many experts believe it already

is happening. They say immigration merely prolongs the inevitable. Since

large-scale Latin American immigration will not continue forever, they

contend, Spanish in the United States will eventually decline. Only major

changes in language attitudes and policies will prevent this. They point

out that a script similar to that followed by previous immigrants is being

played out as U.S.-born Hispanics, for whom English is almost always the

language of choice, seldom pass on Spanish to their offspring.

Recent studies by sociologists Alejandro Portes in Miami, and Rubén

Rumbaut in San Diego, point to a rapid shift to English among the children

of immigrants.

"All

research during the last 30 years...points toward the irrevocable intergenerational

loss of Spanish here," wrote Daniel Villa of New Mexico State University

in one of many responses VISTA received after the posting of an inquiry

on the Internet. Though Villa is conducting research that suggests it may

not be happening any more, Michael Newman, a professor at New York University,

sees evidence daily that Spanish is being lost. "It seems to me that

Spanish is already following the usual immigrant pattern, in New York at

least. I have in my classes any number of semi-speakers of Spanish and

non-speakers who are Hispanic in origin. I have very few, if any, fully

bilingual second-generation speakers."

"All

research during the last 30 years...points toward the irrevocable intergenerational

loss of Spanish here," wrote Daniel Villa of New Mexico State University

in one of many responses VISTA received after the posting of an inquiry

on the Internet. Though Villa is conducting research that suggests it may

not be happening any more, Michael Newman, a professor at New York University,

sees evidence daily that Spanish is being lost. "It seems to me that

Spanish is already following the usual immigrant pattern, in New York at

least. I have in my classes any number of semi-speakers of Spanish and

non-speakers who are Hispanic in origin. I have very few, if any, fully

bilingual second-generation speakers."

Attitudes a Major Factor

Attitudes about language will play a powerful role in

Spanish's future. "I work with bilingual education programs in the

Northwest," wrote Gary Hargett of Portland, Ore., "and I have

observed that Spanish-speaking children soon begin choosing English among

themselves, even when there is permission, even encouragement, to use Spanish.

I think children readily perceive that English is the language of privilege

and power. That would bode ill for the future of Spanish."

A less than enthusiastic attitude about Spanish seems to be shared even

by some who have had wide exposure to the language. Jorge Guitart teaches

Spanish at the State University of New York at Buffalo. "My children

and my brother's children, all born or raised here (in the U.S.) have a

passive knowledge of home Spanish...Although they all have a college education

and even have taken courses in Hispanic literature, they don't read anything

in Spanish nor are they interested."

To be sure, there are plenty of contrary examples. College student Richard

E. Oceguera shared his story: "I'm a Latino from California, and was

not taught Spanish as the result of the prejudice my grandparents endured

while growing up in L.A. during the 1930s and 1940s. When they had their

own children, they opted not to pass the language on. It was their way

of 'protecting' their kids from the evils of prejudice. Thus, my parents

didn't have a commitment to Mexican culture and language to pass on to

me. However, as I grew older, I became increasingly concerned with learning

my ancestral language. Since high school (I'm now entering my final semester

of college), I have studied Spanish language and Latino culture. I'm committed

to mastering my language and passing it on to others who too want to learn."

Oceguera's commitment to reclaiming Spanish probably reflects what Steve

Schaufele of Urbana, Ill., had in mind when he wrote: "Given the current

health of the U.S. Hispanic community and the level of its emotional investment

in its distinctive culture, I would say that American Spanish as one of

the principal vehicles of that culture has an excellent chance of surviving

indefinitely."

Yet the case for the fading of Spanish is bolstered by data such as

that from a recent study in Dade County (Greater Miami), Fla. In that traditional

stronghold of Spanish, the study found that only 2 percent of public high

school students graduate as full-fledged bilinguals.

The

Debate over Spanglish

The

Debate over Spanglish

That mixture of languages called "Spanglish," celebrated

by some as poetic and as the real native tongue of U.S. Hispanics, is denounced

by others as a corruption and a brief stop on the road to the extinction

of Spanish. Roberto González Echevarría, a leading literary

critic who holds a chair at Yale University, recently wrote in a New

York Times op-ed piece titled "Kay Possa?!" that "those

who condone and even promote it (Spanglish) as a harmless commingling do

not realize that this is hardly a relationship based on equality. Spanglish

is an invasion of Spanish by English."

Other scholars have argued that the mixing of languages and bilingualism

are not two-way streets. In the case of the United States, Spanish speakers

tend to become bilingual, but English speakers do not. When all the native

Spanish speakers become bilingual, the need to speak Spanish tends to disappear.

It has all happened before. German was once a flourishing language in

the United States. German immigration then slowed to a trickle and World

War I fostered anti-German feelings and English-only measures. Today, more

than 45 million Americans declare their main ancestry as German, but only

1.5 million claim to speak the language. "My heritage is German,"

wrote Pam Lucas of Oregon. "My dad was born into a German-speaking

world in Nebraska in 1915, but...World War I soon halted just about everything

remotely connected to the German culture. I feel cheated my dad couldn't

pass the language and culture on to me. We can wipe out a language in one

generation. I think it is a crime."

A Different Fate for Spanish?

The debate continues over whether Spanish is following

the same path. When U.S. Hispanics reach the 100 million mark-projected

by the U.S. Bureau of the Census to be around 2050-how many will be able

to carry on a conversation, read a newspaper, or write a letter in the

language of Cervantes and García Márquez?

There are reasons to believe Spanish will follow a different course

than German and other immigrant languages. Strictly speaking, Spanish is

not an immigrant language. It was here before English, its presence in

North America preceding the founding of the United States. In the isolated

mountain communities of New Mexico and in towns on the Mexican border,

Spanish has been spoken continuously for hundreds of years. Spanish is

the native language of Puerto Rico: Puerto Ricans are native U.S. citizens.

Among non-English languages in the United States, Spanish has shown remarkable

resilience.

In

addition to tradition, Spanish has advantages Polish, German, or Italian

did not enjoy at the turn of the century. The sheer size of the Spanish-speaking

population worldwide, the communications revolution and the emergence of

a global economy mean there are more opportunities to use the language

and more economic incentives for retaining it. "It is for these reasons-proximity,

globalization, and new economic structures-that I think Spanish will be

very different in the U.S. from German and other languages of immigration,"

wrote Joseph Lo Bianco, an Australia-based expert who has studied the issue

of languages internationally.

In

addition to tradition, Spanish has advantages Polish, German, or Italian

did not enjoy at the turn of the century. The sheer size of the Spanish-speaking

population worldwide, the communications revolution and the emergence of

a global economy mean there are more opportunities to use the language

and more economic incentives for retaining it. "It is for these reasons-proximity,

globalization, and new economic structures-that I think Spanish will be

very different in the U.S. from German and other languages of immigration,"

wrote Joseph Lo Bianco, an Australia-based expert who has studied the issue

of languages internationally.

The Free Trade Area of the Americas-stretching from Alaska to Patagonia

and scheduled for implementation in 2005-will lead to more cultural interaction,

increase the demand for bilingual personnel in the United States, and reduce

the chances for a radical decrease in immigration from Latin America.

Immigration's Key Role

Immigration is the single most important factor working

in favor of Spanish in the United States. About half of the 700,000 to

one million legal immigrants who arrive annually come from Spanish-speaking

countries. The percentage is higher for the estimated annual flow of 300,000

undocumented immigrants, according to Immigration and Naturalization figures.

The supply of newly arrived Spanish speakers will not dry up any time

soon. Though the U.S. Congress in 1996 passed the toughest immigration

laws since the 1920s, legal immigration ceilings were not reduced at all.

But as the Hispanic presence in the United States continues to rise through

immigration and high birth rates, there are sure to be renewed calls for

ending immigration.

For now, population trends, especially in certain areas of the country,

point to a long life for Spanish. "In California, Latinos are growing

twice as fast as whites," wrote Gene García of the University

of California at Berkeley. "The state predicts that the school population

will be majority Latino by 2008. This population remains mostly first-generation

immigrant...therefore, young children are likely to learn Spanish or become

bilingual...The best predictor of a vitality of a language is whether that

language is spoken by young children."

Whether young children learn the language depends primarily on the family.

The most effective way to raise a bilingual child is for the parents to

consistently speak to him or her in Spanish in the home and to provide

a variety of reading materials in that language.

Keeping

Spanish Alive

Keeping

Spanish Alive

Another key factor in Spanish's long-term future here

is the availability of programs to teach Spanish to native speakers. Since

the early 1980s, there has been a legislative and educational backlash

against bilingual programs, which some say hinder learning. Yet, an impressive

body of literature indicates that well-crafted bilingual programs can increase

educational achievement and help students develop the home language.

In the United States, non-English languages always have existed alongside

English, but their presence has been seen more as a temporary inconvenience

than as a valuable national resource. Critics of bilingualism ask why Spanish

should be any different. "The U.S. is an English-speaking country,"

wrote Meg, an English as a second language teacher. "The idea that

one might immigrate to a new country and impose one's own language should

have been outlawed."

The attack on bilingual education continues to intensify. Ron Unz, an

unsuccessful candidate for California's Republican gubernatorial nomination,

is gathering signatures to place an initiative on the ballot to eliminate

bilingual education.

Cecilia Pino, an associate professor of Spanish who founded and directs

the Spanish for Native Speakers Institute at New Mexico State University

in Las Cruces, draws a sharp distinction between bilingual education and

Spanish for native speakers programs. "Our emphasis is on the need

to maintain our heritage language. We don't do any English language instruction."

The key to successfully teaching Spanish starts with valuing each student's

dialect and working from there to develop skills for use in academic and

professional settings. Too often students have been told their Spanish

is wrong, discouraging them from learning the language. In some schools,

students have been punished for speaking Spanish in the classroom.

James L. Fidelholtz, a linguist at the Universidad Autónoma de

Puebla in Mexico, says there are many reasons Spanish will survive, but

cautions, "All this is not to say that the virtual extinction of Spanish

in the U.S. is impossible...The best way to avoid this tragic fate...is

to widely publicize the great and real benefits for all which bilingualism

brings."

Perhaps the best answer to the question of Spanish's future in the United

States is that it depends on us. As Steve Schaufele wrote: "As a general

rule, a language will survive if the community that uses it cares enough

to invest effort to maintain it."

Will we?

Max J. Castro , Ph.D., is a senior research associate at the North-South

Center at the University of Miami.

Despite

the boom in Spanish, no one questions the continuing dominance of English

in the United States and internationally. English is the lingua franca

in the world today. Its status is ensured by its use in cutting-edge areas

such as science, aviation, and computers. Checking out the Internet's World

Wide Web? About 83 percent of home pages are in English. No language in

human history has ever had the global standing English currently enjoys.

Despite

the boom in Spanish, no one questions the continuing dominance of English

in the United States and internationally. English is the lingua franca

in the world today. Its status is ensured by its use in cutting-edge areas

such as science, aviation, and computers. Checking out the Internet's World

Wide Web? About 83 percent of home pages are in English. No language in

human history has ever had the global standing English currently enjoys. The

fate of immigrant languages has been to flower, then fade. Will that be

the story of Spanish in the next century? Many experts believe it already

is happening. They say immigration merely prolongs the inevitable. Since

large-scale Latin American immigration will not continue forever, they

contend, Spanish in the United States will eventually decline. Only major

changes in language attitudes and policies will prevent this. They point

out that a script similar to that followed by previous immigrants is being

played out as U.S.-born Hispanics, for whom English is almost always the

language of choice, seldom pass on Spanish to their offspring.

The

fate of immigrant languages has been to flower, then fade. Will that be

the story of Spanish in the next century? Many experts believe it already

is happening. They say immigration merely prolongs the inevitable. Since

large-scale Latin American immigration will not continue forever, they

contend, Spanish in the United States will eventually decline. Only major

changes in language attitudes and policies will prevent this. They point

out that a script similar to that followed by previous immigrants is being

played out as U.S.-born Hispanics, for whom English is almost always the

language of choice, seldom pass on Spanish to their offspring. "All

research during the last 30 years...points toward the irrevocable intergenerational

loss of Spanish here," wrote Daniel Villa of New Mexico State University

in one of many responses VISTA received after the posting of an inquiry

on the Internet. Though Villa is conducting research that suggests it may

not be happening any more, Michael Newman, a professor at New York University,

sees evidence daily that Spanish is being lost. "It seems to me that

Spanish is already following the usual immigrant pattern, in New York at

least. I have in my classes any number of semi-speakers of Spanish and

non-speakers who are Hispanic in origin. I have very few, if any, fully

bilingual second-generation speakers."

"All

research during the last 30 years...points toward the irrevocable intergenerational

loss of Spanish here," wrote Daniel Villa of New Mexico State University

in one of many responses VISTA received after the posting of an inquiry

on the Internet. Though Villa is conducting research that suggests it may

not be happening any more, Michael Newman, a professor at New York University,

sees evidence daily that Spanish is being lost. "It seems to me that

Spanish is already following the usual immigrant pattern, in New York at

least. I have in my classes any number of semi-speakers of Spanish and

non-speakers who are Hispanic in origin. I have very few, if any, fully

bilingual second-generation speakers." The

Debate over Spanglish

The

Debate over Spanglish In

addition to tradition, Spanish has advantages Polish, German, or Italian

did not enjoy at the turn of the century. The sheer size of the Spanish-speaking

population worldwide, the communications revolution and the emergence of

a global economy mean there are more opportunities to use the language

and more economic incentives for retaining it. "It is for these reasons-proximity,

globalization, and new economic structures-that I think Spanish will be

very different in the U.S. from German and other languages of immigration,"

wrote Joseph Lo Bianco, an Australia-based expert who has studied the issue

of languages internationally.

In

addition to tradition, Spanish has advantages Polish, German, or Italian

did not enjoy at the turn of the century. The sheer size of the Spanish-speaking

population worldwide, the communications revolution and the emergence of

a global economy mean there are more opportunities to use the language

and more economic incentives for retaining it. "It is for these reasons-proximity,

globalization, and new economic structures-that I think Spanish will be

very different in the U.S. from German and other languages of immigration,"

wrote Joseph Lo Bianco, an Australia-based expert who has studied the issue

of languages internationally. Keeping

Spanish Alive

Keeping

Spanish Alive